Trade War Static: Stay Focused On the Big Picture

Just as markets seemed to be happily pricing in a resolution to the yearlong trade conflict between China and the United States, fresh difficulties have emerged, throwing the outcome into doubt. Global stock markets swooned in response to the tweets… a phenomenon with which investors have become familiar over the past two years.

What’s an investor to do when so much apparently hinges on contentious diplomacy and unpredictable political negotiating tactics?

Our response is, almost invariably, to keep attention focused on the big picture: the economic realities, the deeper trends, and the long-term character and interests of the relevant actors — whether countries or individual politicians.

In the case of the U.S./China trade conflict, then, let’s step back from the news that’s roiling markets today (and may well roil them in the opposite direction tomorrow) and look at the most significant elements of the big picture.

The Economic Backdrop in the U.S. and China

As we wrote last week, the economic backdrop in the U.S. is basically very positive. The preliminary results for first-quarter U.S. GDP growth came in at 3.2%. We do not anticipate that this pace of growth will be maintained throughout 2019; we see a growth rate of 2.5–2.75% for the full year. Still, the U.S. economy is clearly capable of sustained growth above the low levels that were characteristic of the years following the 2008–2009 recession. Other economic indicators are also positive for the U.S. Employment continues to improve, the sentiment of consumers and small business owners is strong, and wages are rising.

China presents a somewhat different picture. Over the past two decades, China has transitioned from being a totalitarian political system with a command economy, to a totalitarian political system with an economy that has significant free-market elements. Much of the Chinese economy and financial system have been a “wild west” affair. In this economy, as in the rest of the world, small and mid-sized businesses have been the great engines of growth and prosperity. The state-owned enterprises are still present, and are still very systemically important and influential, but they are not the place where the rapid growth has occurred that has lifted so many Chinese citizens out of poverty.

To fund growth in these dynamic businesses, China has allowed the wild expansion of credit in the “unofficial,” or “shadow-banking” sector of its financial system. Chinese citizens, who are generally great savers (as well as enthusiastic speculators), have also resorted to the shadow-banking sector as they seek better returns than they would get from the official banks. While this process has enabled remarkable growth, it has also created grave risks of financial instability, as leverage in the system has increased.

The Chinese government is well aware of these risks. So the Chinese economy in recent years has been the story of a delicate and fraught balance between growth on the one hand, and the risk of a financial crash on the other. (A financial crash which resulted in a severe economic slowdown could pose an existential threat to the stability of the Communist Party’s rule, so this is something the government wants to avoid at almost any cost.)

The government has periodically acted to rein in the shadow bank lenders — action which slows growth — and then loosened up again — action which encourages growth. Their goal is to maintain a high enough growth level to keep the population happy, and to keep bringing more of China’s poor into their middle class — while avoiding financial catastrophe. Thus far, they have succeeded.

Last year saw the Chinese government turn away from a tightening phase, to a loosening phase — although with a new, somewhat milder set of policy tools in which they have tried to allow credit growth without enabling speculative excesses, for example in the real estate sector. As economic indicators continued to lag last year, we continued to believe that we would see a reacceleration later in 2019, and this is still our base case scenario.

In short, as we look at the economic backdrop to trade negotiations, we should keep in mind that the U.S. is negotiating from a position of current strength, while China’s position is more tenuous. This reality is certainly coloring the psychology and the approach of negotiators on both sides.

On the Ground: The Actual Effects of Trade Actions Thus Far

Both sides have taken action thus far — this conflict has been more than mere saber rattling. What effect have those actions really had on the countries’ respective economies?

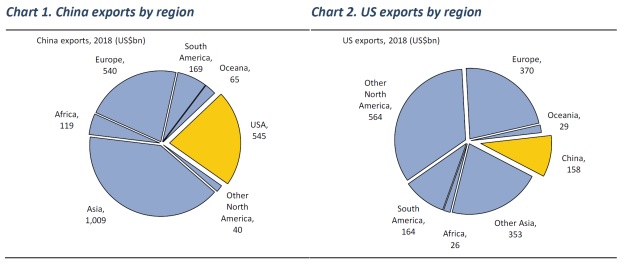

In 2018, as Jonathan Anderson at Emerging Advisors Group points out, the U.S. was the destination for about 22% of China’s exports — while China (including Hong Kong) was the destination of only about 9% of the U.S.’ exports.

Source: Emerging Advisors Group

On this level, China has more to lose from tit-for-tat tariffs than the U.S.

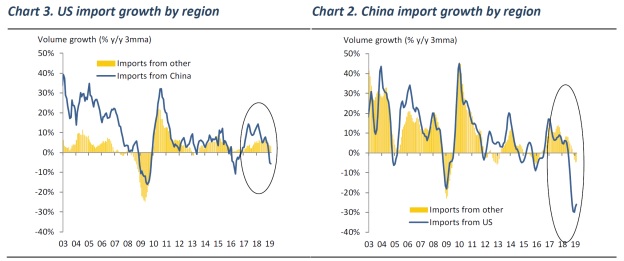

On the other hand, when we look at actual import volume growth, we see that China’s imports from the U.S. have fallen off a cliff, while U.S. imports from China have declined only slightly. As Anderson puts it: “There’s no real evidence to date that tariffs have had any impact on U.S. spending patterns.”

Source: Emerging Advisors Group

So on the ground, we can basically say that the trade war has been a draw thus far.

Personalities and Red Lines

There are larger-than-life personalities involved here, and obviously their statements and actions have market-moving consequences.

First and most obvious is President Trump. We have long said that we do not regard his style as inscrutable or wholly unpredictable, although he seems to relish it when he’s characterized that way. Put frankly, his style of negotiation freaks out market participants. However, we have been saying since 2016 that we see themes in his style that have been consistent for decades and are clearly present in his book The Art of the Deal.

These themes are in full display in the current high-stakes negotiation with China, and in the sudden change of direction last Sunday (which was not actually a change of direction at all). Mr Trump likes to wrong-foot his opponents. He likes to raise the stakes at the last minute to get a better deal; he likes high pressure. He takes the negotiations personally, and often seeks to rely on personal connection, and personal give-and-take, with individuals across the negotiating table. It remains to be seen whether these tactics will work in international trade the way they may work in domestic U.S. real estate transactions, but Mr Trump seems to believe that nothing else has really worked to restrain China’s unfair trade practices over the decades, and even his political opponents in the U.S. seem willing to let him try something new.

Trump Looks To Personal Ties To Cement Deals

Source: Xinhua

The balance for Mr Trump, we believe, is that he is personally motivated to secure a deal that he can present to the American public as an improvement over the status quo. He is convinced that he is negotiating from a position of strength; it is probably not a coincidence that he felt able to ratchet up tensions immediately after the strong U.S. GDP and jobs data were released. He has also been passionate about securing more fair trade with China for decades, with a consistency that he has shown in few other areas of public policy.

However, his history of negotiating, both as President and before, shows that he cares more about closing a deal than about getting everything he wants, whatever noise he may make during the negotiations. Basically, Mr Trump is playing hardball because that’s his style — but he wants a deal and will take the best one he believes he can get, and that he can sell as a victory.

On the Chinese side, there is less riding on President Xi’s personal style, and more on the situation in which the Chinese Communist Party finds itself. The Party needs growth, and they know that the growth strategy of the last two decades, of expanding leverage in the shadow banking system, has reached a point of rapidly diminishing returns and rapidly increasing risks.

A deal will help facilitate a path forward to China’s real goal — to enable further growth without relying on the creation of destabilizing debt. China’s rulers know, on some level, that future growth depends on the kind of convergence with the standards of the rest of the global economy that their negotiating partners are demanding of them. That’s one reason they consistently offer pronouncements of their commitment to economic openness — as President Xi did recently to a conference of regional leaders convened around China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Is it just lip service? Only in part. There are some areas that will remain persistent problems — intellectual property, for example — but others areas where they will be more willing to move towards U.S. demands, especially where they see that it will serve the continued growth of their middle class and a more consumer-facing economy. (Which does not, of course, imply any necessary liberalization of their domestic political environment.)

We note also that the areas in which the U.S. is accusing China of “renegotiating” at the last minute, are agreements that they were previously willing to make, which means they are probably not real “red lines” that they’re absolutely unwilling to cross.

Investment implications: Investors should not be unduly panicked by the ebb and flow of trade negotiations between the U.S. and China. Our base case remains that a deal is made which both sides can present as a victory, because we believe that both sides are highly incentivized to reach such a deal. The probability of near-term disruption has increased, but we do not view the risk of a delay in a deal as a systemic risk for markets, and given the consistently strong economic and financial backdrop in the U.S., and the improving economic backdrop in China, we would regard weakness as a buying opportunity.