Narendra Modi and the Bharatiya Jannata Party [BJP] took the reins of India’s government in May, 2014. Since then, we’ve been bullish on the long-term opportunity that would be presented by India’s emergence from the corruption and business-hostile governance of many of its 20th century rulers.

Some readers may have forgotten about the momentous character of the political shift that took place in 2014, and was re-asserted with sound BJP electoral victories in April and May of 2019, extending Mr Modi’s reform mandate still further.

After his 2014 victory, we wrote:

“The new Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi of the Bharatiya Janata Party [BJP], is known for the economic growth that he brought to the state of Gujarat as its Chief Minister from 2001 to 2014. In those 13 years, Gujarat, which lies directly to the south of Pakistan, has far outperformed the rest of India — and especially its neighboring states in India’s north.

“In Gujarat, he cut corruption, built infrastructure, actively encouraged investment (both Indian and foreign), and encouraged new business.

“He was successful in raising the standard of living of his constituents substantially. This has led to his national popularity. During the same period India’s overall growth has slowed under its famously slow-moving, corrupt, ponderous, inefficient national bureaucracy — a bureaucracy which has been encouraged and expanded by the India National Congress Party [INC] during its decades of political dominance.

“Young Indians were fed up, and it is they who voted for more free markets and less red tape when they handed victory to the BJP…

“He will work to cut back rent-seeking, streamline government, and make it easier for business to come to India and create prosperity for Indians — much as strong leadership in China has done for the Chinese. He will lower taxes and increase government accountability, and he will cut red tape. One of his first acts will be to go after tax evaders who hide money in nearby tax havens.

“The INC, and its policies of buying votes with handouts including cash, fuel, and food subsidies, was badly defeated at the polls after ruling for the great majority of the last 60 years. In spite of India’s remarkably able people and intelligent entrepreneurs, India has not enjoyed an economic growth rate anywhere near China’s. Over the past 30 years, the Chinese have seen their per capita GDP rise from $300 to $6,750, while India’s has been stagnant in comparison — rising from the same $300 starting-point to about $1,500…

“The basic dynamic keeping India’s economy in a rut is the opposing forces in the form of corrupt bureaucrats and political leaders, who hold up many projects until they find a financial reason to implement them.

“Modi ran on a platform of less handouts, cutting corruption and a much bigger focus on providing the infrastructure necessary attract foreign direct investment in India. Albeit decades later than China, India is planning to do the same kind of strategy which proved wise in China — build out the country’s infrastructure and open up to more foreign investment.

“It is not likely to be as easy as it has been in China — which is top-down managed economy where the upper echelons dictate to the rest of the economy how to allocate resources. India is, to put it simply, a mess — a huge democracy with many poor, uneducated, and illiterate voters. But in spite of Modi’s stated plan to cut subsidies for fuel, food, and other necessities, and to spend the money on developing the country’s infrastructure, voters put him into office…

“A great deal of work needs to be done; but if successful, India has the potential to become the great growth opportunity in Asia for the next decade. We will watch developments carefully… Longer-term, we will wait to see how successful Modi is in attacking and dismantling India’s famously slow and corrupt bureaucracy.”

Structural Reforms: Making Progress

Much of what we wrote in 2014 was prescient. Modi’s course over the past five years has indeed not been easy. Modi’s second-in-command, the Home Minister, Amit Singh, referred to a process of “detoxification of the economy” — and that it an appropriate description of what Modi has had to undertake over the past five years.

It has been a tough period for the Indian economy and for the Indian financial system, both because of the painful reforms the Modi administration has made, and because of international trends (such as the uncertainty surrounding global trade over the past two years.) Third-quarter data from this year show real GDP growth of only 4.5% — 3.1% when government spending is stripped out. But this slowing growth is attributable to the near-term pain caused by Modi’s long term structural reforms — which, if they work and are maintained, will be delivering growth dividends far into the future.

Modi’s government has shifted the ground under Indian business. Big businesses were used to an environment of corruption, and came to depend on it, slowing the economy and diverting capital from better operators. A new bankruptcy law — and decisions handed down by India’s Supreme Court — have made it clear that political connections will no longer suffice to protect India’s cronies. The same is true of the BJP’s aggressive approach to tax collection, and the “demonetization” efforts to drive economic activity out of the tax-free underworld and into the light of day. The activities have put some salutary fear into the hearts of many crony capitalists, to the extent that Mr Singh recently offered public reassurances that the cleanup was winding down.

The rule of law, good regulatory order in Indian finance and taxation, and sound bankruptcy proceedings will be a very good thing long-term, but there is no doubt that they have had a chilling effect on growth in the near term. In particular, the housing market has struggled, as demand has sagged now that housing is used less to park gray money. Of course, the housing market here, as elsewhere in the world, is an economic engine, and many India watchers are waiting for a residential property rebound to help drive construction activity.

When will the cycle turn? It may be a few quarters yet. The BJP is, more than many of the world’s ruling parties, cautious of moral hazard, and not eager to engage in fiscally profligate behavior. Some are calling for more fiscal stimulus, including income tax cuts, or for TARP-like bailouts of some Indian banks reminiscent of the action taken in the U.S. in 2008 to strengthen its banking system.

Still, the government is pressing ahead in its reforms — for example, in its plans to divest government stakes in big public-sector companies.

How Have Indian Stocks Done?

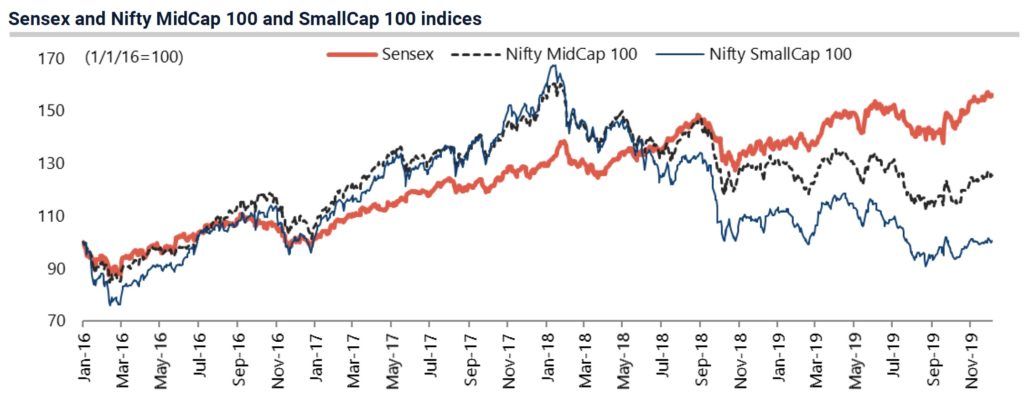

The Indian stock market has held up well for the past few years — at least the large Sensex index. Mid-sized and small companies have fared worse, bearing more the of the brunt of the reform-related slowdown.

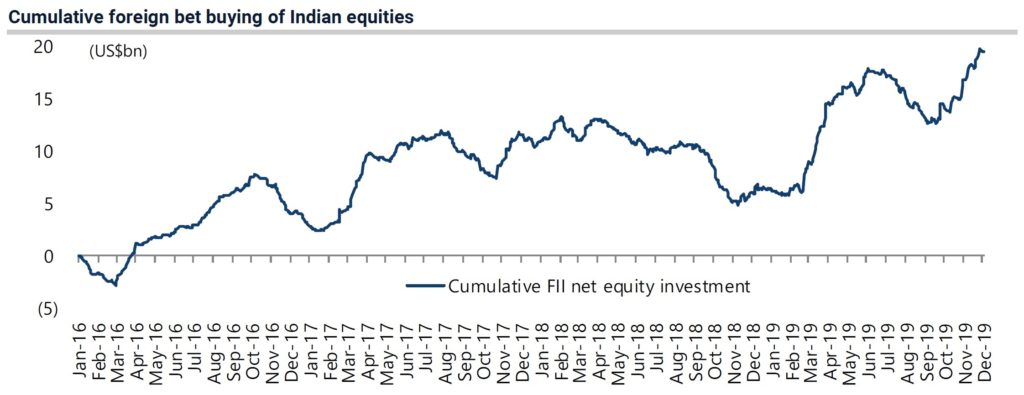

Buying has been supported both by foreigners, and by the government’s demonetization, which has increased the appeal of the stock market as a destination for formerly hidden cash.

While it’s encouraging to see stock market participation, markets will likely want to see more signs of progress if they’re going to sustain current valuation levels — or give the stocks of small and mid-sized businesses the chance to catch up.

Investment implications: The difficult structural reforms of the Modi government in India have resulted in some pain for the Indian economy. This was unavoidable, although the effects of some reforms have been more severe than the government anticipated. We remain very bullish on India’s long-term prospects, assuming that the current government remains in power and continues to push its reform agenda. In the near term, there may be several more quarters of relative pain ahead for the Indian economy. It may take longer for Indian business owners and the Indian financial system to adapt and feel steady in a “new normal” where much habitually corrupt behavior has been curtailed. Given the currently high valuation of the Indian stock market — and especially the stocks of big companies that are available for foreign ETF buyers — we are tactically cautious on Indian stocks.