There seem to be plenty of reasons for pessimism right now.

Even just on the surface, so much disaster and risk: a global pandemic… political polarization at all-time highs… an election coming up so fraught that both sides are talking about civil unrest if the result is not immediately clear… riots, looting, arson, gang violence, and police brutality in all the headlines… Wall Street screaming to new highs while Main Street is pummeled by lockdown-induced recession, unemployment, and a small-business apocalypse… central bank balance sheets and government deficits on a rocket sled to the moon… billionaires getting richer while working stiffs subsist on unemployment handouts and “UBI lite”… depression, domestic violence, and suicides all up. Pick your poison: each side of the aisle has a tale to tell about how terrible everything is, how we’re all doomed, and how it’s all the other side’s fault. Perhaps we could summarize it with a bumper sticker we’ve seen a few times:

(And for those who need it, never fear — there are already reports that a helpful giant meteor is indeed on the way in time for the election.)

For investors, though, participating in this depressive, pessimistic hive mind can have very negative consequences. Particularly for stock-market investors, since investing in stocks is the most direct way to benefit from the wealth-creation engine of freedom, ingenuity, and the rule of law (which we still enjoy). Stepping aside from participating — sitting on the sidelines because of plausible narratives of impending doom — is the surest way to escape the curse of long-term gains.

When there is money to be made, pessimism will keep you from making it.

Here are a few observations about this currently fashionable pessimism, and our rebuttals — to encourage investors to make a properly optimistic bet on progress, ingenuity, humanity, and prosperity, even though we don’t know whether tomorrow will bring a correction, a crash, or further new highs.

First: we have all become nearly constant media consumers, and the media’s longstanding motto is “if it bleeds, it leads.” That means that the never-ending news stream that you carry around in your pocket and look at in every spare moment is intrinsically biased to the negative. (And in case you think it’s only commercial media that are guilty, the BBC is among the worst offenders.) Big data analysis has actually shown this: the sentiment of news stories has been trending down for decades and started getting even more negative with the birth of the internet. Interestingly, the same analysis of dated historical events in Wikipedia shows sentiment about those events getting more positive over the past century and a half. Our takeaway? The world is getting better, but the media want you to think it’s getting worse. (We’ll be looking closely at the readership of this edition of our newsletter to see if we’ve shot ourselves in the foot by coming out as optimists.)

Second: it sounds smart to be a pessimist. Perhaps there is a biological, evolutionary bias towards seeing dangers more clearly than opportunities. Behavioral economics suggests this when it has found that people are more averse to loss than they are eager for gain. There are always clever-sounding descriptions of unsuspected dangers that make their cautious, skeptical promoters sound wise. But when it comes to investing, we are not in the market for wisdom. We are in the market for financial success. The innate tendency to see danger is short-term, and misses the bigger trajectory of cultural, economic, and historical progress.

Third: the market is “expensive.” Yes, the market is expensive on a simple comparison of present to historical mean price-to-earnings multiples. Its valuation on a forward basis is uncertain because the growth trajectory of the global economy post-lockdown is uncertain. Ostensibly, all of the gains since the March lows have been multiple expansion. But here’s the rub — what is the proper multiple to ascribe to earnings in a situation where interest rates are expected to remain pinned near zero for the foreseeable future, and central banks continue to create enormous liquidity through ongoing asset purchases and credit-market backstops?

It is this question which caused Canaccord Genuity strategist Tony Dwyer to suspend his 2020 target for the S&P 500. In a note on August 31, he commented, “A zero-interest rate policy and unlimited QE have no precedent, rendering valuation targets useless” (this is what it sounds like when someone with market experience, rather than academic economic knowledge, is speaking). Bank of America strategist Ajay Kapur noted on the same day, “Looking at raw valuation metrics without a cost of equity is just plain lazy. Valuations are a function of liquidity, returns on capital, the cost of capital, sentiment, inflation, and GDP volatility… Simple valuation metrics compared to their history might be a convenient shortcut, but a dangerously simplistic one, [and should not be used] as a crutch for elegant pessimism.”

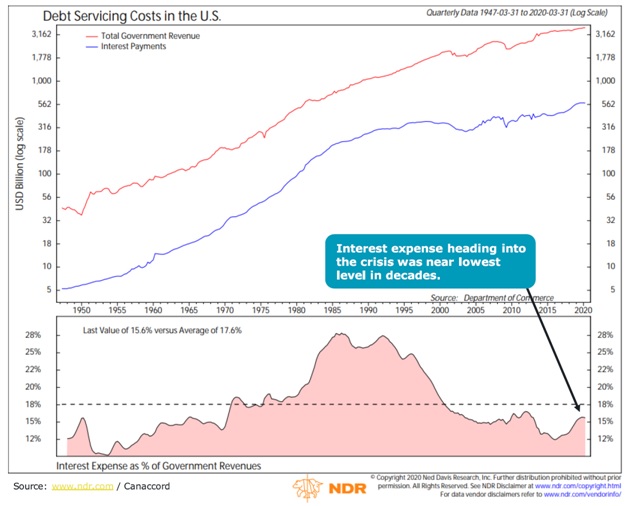

Fourth: debt is growing to unsustainable levels that will crush future economic growth. This actually falls under the rubric of “it sounds smarter to be pessimistic,” but we will address it anyway. The key point here is simply that what matters most is debt servicing costs… and those remain historically very low and manageable, thanks to zero-interest rate policies.

While we’re not sanguine about inflecting debt levels, our simple point is that they are not a sign of imminent doom. Alarmism to the contrary, the U.S. is actually very far from tipping into a scenario where economic growth or financial stability are threatened by the cost of debt service, or the mechanisms used to keep it under control.

The pessimistic points that concern us the most are actually psychological rather than economic or financial. It’s not so much that doom is upon us, because we’re pretty sure it isn’t. It’s more that so many citizens believe that doom is upon us. In the face of doom, some very important things go out the window, such as widespread social trust, and devotion to a non-violent political process in order to achieve the political and social goals in which one believes. High-trust societies and societies with the rule of law — rather than the rule of force — are more prosperous and better to live in. The voices counselling otherwise need to be resisted. (Non-violently.)

Still, these concerns also fall under the rubric of “if it bleeds, it leads.” The media would have us believe that the polarization of our politics is far more acute than it actually is. A national organization called Braver Angels facilitates daylong workshops between groups representing the opposing sides of American political discourse on various issues. Their experience has shown that even a single day of actual face-to-face communication causes opinions to converge and sympathy for opposing views — and those who hold them — to rise. Is America coming apart at the seams? It certainly can seem so to those who remain in their increasingly comfortable echo chamber (and those who are watching from a safe distance overseas), but seems less so to those who step out of it.

Investment implications: 2020 has thus far been a year that has seemed to encompass a series of terrible scenarios — pandemic, market crash, government responses with which everyone seems to disagree, social strife, economic seizure, and political polarization. For many reasons, investors’ responses to these can be collapse, capitulation, and exit from stock markets. We think the prospect of doom is vastly overstated, and that pessimism as a mindset is not conducive to success as an investor. Corrections and rotations may come, and they are becoming more likely as markets continue their giddy climb to new highs. But that does not mean that the story of impending doom is correct, and investors should be very careful not to shut themselves out of stock-market gains because they absorb the “elegant pessimism” of the pundits.