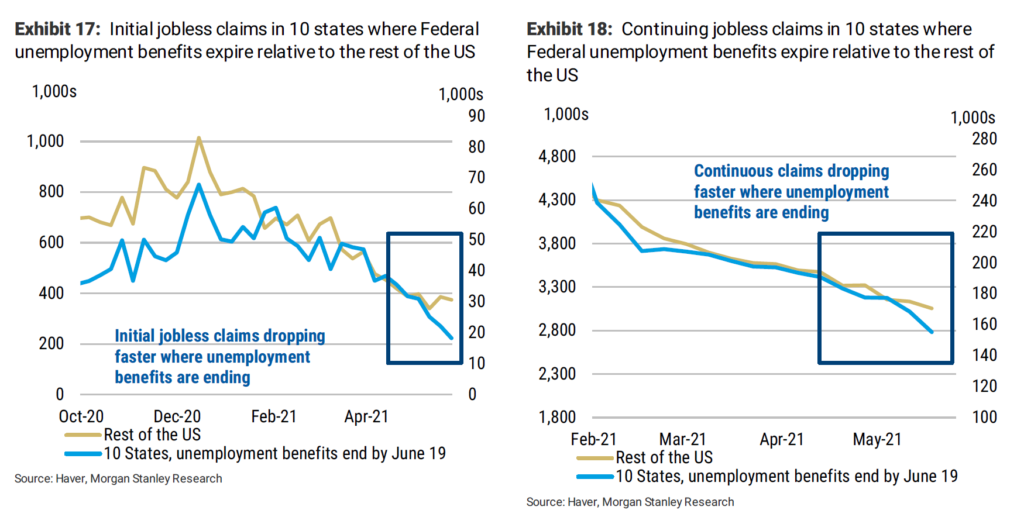

As many states have now ended the additional pandemic unemployment benefits provided by the Federal government, we are seeing in real time that those benefits were in fact serving to suppress employment and encourage workers to stay home; unemployment is falling faster there than in states that have maintained the benefits:

Employment May Improve Faster Than Expected

We believe that as this process unfolds it will cause unemployment to fall faster than many expect, and that by the time of August’s confab in Jackson Hole, WY, the Fed (or various FOMC members) will be talking more seriously about tapering and perhaps telegraphing more detailed information about the timing of rate increases, even if those do not come before 2022.

Further, September will mark the return of students to school, and when Federal supplemental benefits will end in those states which have not ended them earlier. High labor-market demand (9.2 million job openings) has encouraged more workers to be willing to quit their jobs, and as we have reported for some time, regional migration in the U.S. is ongoing, with families decamping from states with higher regulatory and tax burdens and moving to states they perceive as more congenial, such as Texas, Arizona, Florida, Utah, and the south and southeast. Vaccines will have been available for long enough this fall that we believe all who want to receive them will have done so.

All these trends suggest to us that August and September will be an important one to watch for inflections in macro trends and Fed policy communications.

A Fall Correction?

That, in turn, suggests that the risk of a market correction will rise. Last week we pointed out that the liquidity peak has already arrived — in the sense that its pace of expansion has already started to decline. Should Fed officials begin discussing tapering and tightening more explicitly, and begin walking forward expectations for rate increases, volatility becomes a greater risk.

Recent (post-2008) history bears this out. 2011 saw a five-month, 19% correction after the Fed discussed not expanding QE. Balance-sheet reduction talk preceded a one-month, 12% correction in 2015. Late 2018 saw a three-month, 20% decline on the balance-sheet “autopilot” comments. And in the fall of 2020, with the Fed balance sheet down due to the unwind of certain crisis policy facilities, we had a 10% decline. When the market runs on liquidity, changes in liquidity — absolute levels, growth direction, and pace — have outsize effects on volatility.