Last week, the European Central Bank joined the U.S. Federal Reserve in moving toward a policy regime that’s more tolerant of inflation. Rather than a 2% ceiling, the ECB will now target an average rate of 2%, tolerating overshoots to compensate for periods of lower inflation. (The Fed’s move to a similar policy was announced back in April — though the Fed goes a step further in targeting rather than merely “tolerating” overshoots.)

Especially in the case of Europe, it’s far from clear that the tools at their disposal will actually be able to generate the inflation to be “tolerated,” so it is likely that these policies are either (1) an exercise in public relations to encourage the market to create the effect that central bankers are looking for, or (2) will eventually have to be supplemented with other tools.

Of course, their main fear is not inflation, but disinflation (persistent inflation below their target) or deflation (outright falling prices). They are not the only ones with this fear — no one has any appetite for disinflation, not central banks, nor the private banking system, nor indebted corporations, nor indebted private citizens, nor indebted governments. Why?

The simple answer is debt, and the prospect of future debt in the form of “unfunded liabilities.” This is a topic we have touched on many times, so we’ll just summarize briefly here.

Inflation: The Debt Solution

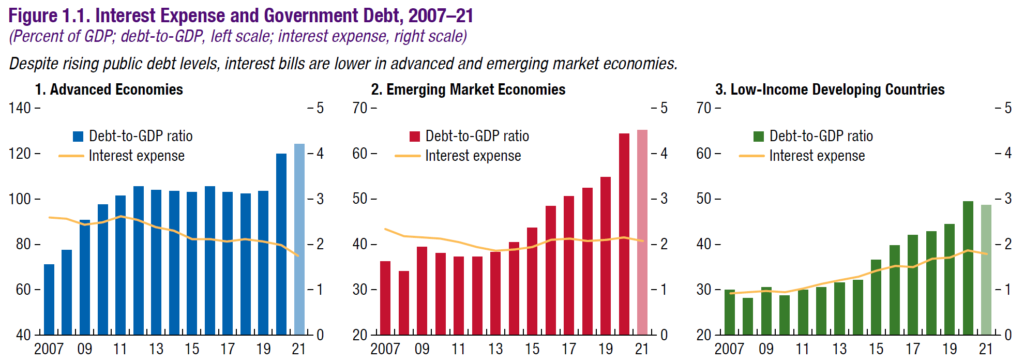

Although global levels of individual, corporate, and government debt have been rising for decades, pandemic policies have raised them to a new pitch. The first year of the pandemic saw global debt expand with extraordinary speed — globally, from about 87% of GDP to an expected 99% of GDP by the end of 2021. Of course, debt levels are highest in developed countries; less developed countries are unable to take on greater debt burdens because global investors demand higher interest rates for the higher risk posed by their economies and governments. But the point is that across both developed and developing countries, debt levels are at historic peaks.

Globally, the peak is just shy of the debt maximum reached at the end of the Second World War:

Naturally, indebted people prefer inflation to deflation, because under inflation, they can repay debt with cheaper dollars, pounds, euros, and yen. Of course, that is part of the design.

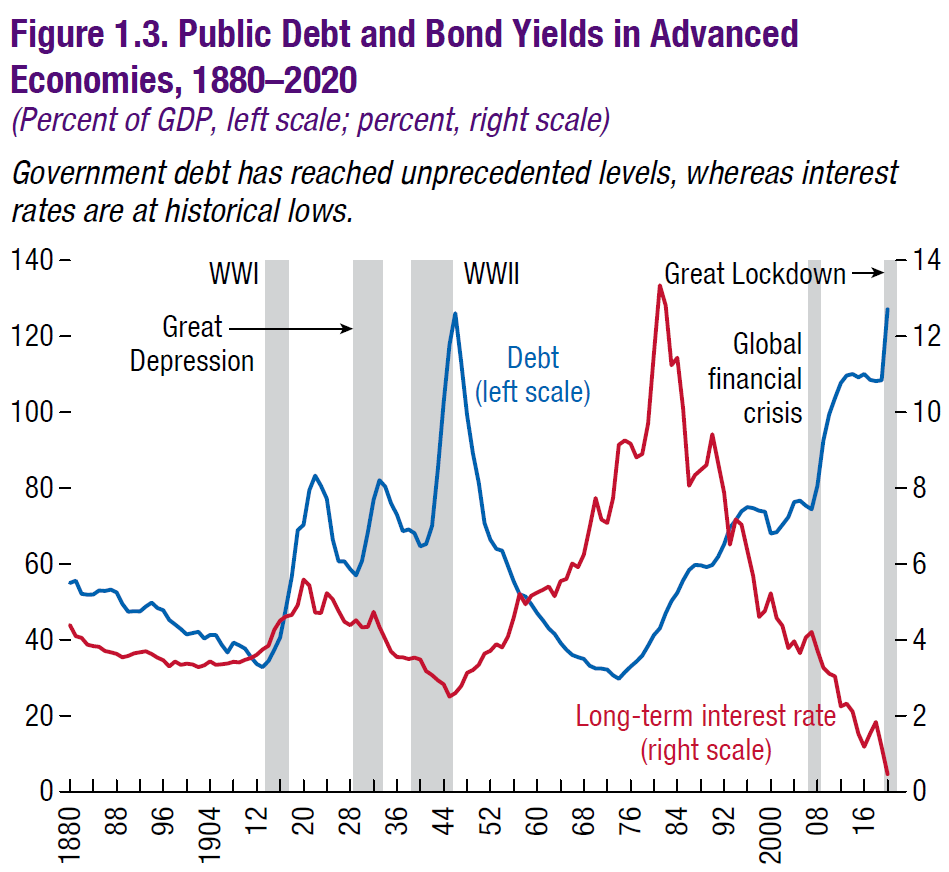

Highly indebted nations after the Second World War engineered a lengthy period of moderate inflation to gradually reduce public and private debt burdens.

That process was helped mightily by an era of strong global growth, led by the industrial expansion of the U.S., the reconstruction of Europe and Japan, and the development of many new technologies which enhanced productivity. Demographics were also favorable, and the burden of social welfare programs relatively light.

The world has reached a new debt peak, with no signs of an impending slowdown in spending. In the U.S., fiscal conservatism is a thing of the past for both parties; the question is no longer “whether” but “how much.” In addition, unfunded liabilities (such as Social Security and Medicare) are now an inescapable part of the landscape U.S. politicians must navigate. Unfunded liabilities and interest payments together may exceed tax receipts in the next decade.

That spending picture also presents a reason for governments to want inflation and fear deflation, since future Social Security and Medicare payments will be indexed to inflation measures that will certainly understate the reality of inflation experienced by the retirees and workers receiving benefits. Put simply, inflation means that benefits can be ratcheted down slowly without needing to pass any laws in Congress or alienate any voters.

Therefore, inflation handles both of the fiscal problems faced by governments around the world — high and rising debt, and high and rising liabilities for social welfare programs. Indeed, inflation is the only politically palatable way out for governments.

Can They Do It?

The history of the post-2008 world might suggest that governments are simply unable to create the kind of inflation they would really like. After all, extraordinary monetary policy has been underway full-force in much of the world; previously unthinkably easy money seems to have become a sine qua non for central bankers; and yet, inflation proved elusive for most of that time.

The reason that this time may be different is that unlike the post-2008 monetary measures, which were enacted without a large fiscal impulse, this time, monetary and fiscal authorities (central banks and governments) are working in a coordinated fashion. That makes the effect much more powerful, and more likely to achieve its goal. These coordinated efforts in the teeth of the pandemic lockdowns last spring told us that we had entered a new era of policymaking — that we had crossed a Rubicon.

Will Interest Rates Cooperate?

The behavior of the U.S. bond market in the face of these developments has been interesting. Over the past few months, we have brought you updates of our in-house inflation measure, the Guild Basic Needs Index (GBNI), which we have designed as a simple indicator of the real-world inflation likely to be experienced by U.S. consumers “on the ground.”

The GBNI has shown that inflation is certainly occurring and higher than official headline numbers suggest — and even those understated headline numbers have been high. Yet in the face of this, the long-term U.S. bond market is quiescent. What is happening?

One explanation is that many non-U.S. investors in countries where interest rates are lower than in the U.S. are engaging in a carry trade. This is trade where non-U.S. buyers buy intermediate-term U.S. bonds (for example, 10-year U.S. Treasuries), and take the extra income the U.S. pays — while expecting the U.S. dollar to rise versus their home currency (for example, euros or yen). This carry trade is appealing because, for example, German 10-year Bunds currently yield −0.29%, while the Japanese 10-year yield is 0.025%. The U.S. rate for 10-years Treasuries is 1.35% as we write. Thus, foreign investor demand is helping keep U.S. 10-year rates low.

Another explanation for U.S. Treasury rate behavior is that many economists, analysts, and investors do not believe that this higher inflation will last. They believe it is mostly being caused by pandemic supply-chain and labor-force disruptions that will resolve themselves in coming months, and that inflation will then return to its old trend.

We do not agree. We believe that the actions and stated intentions of policy makers show great determination to create higher inflation, and we believe the new policy toolkit and spending patterns shown during the pandemic indicate that they have the ability to accomplish their goals. This will not be hyperinflation in the near future; it will be inflation persistently higher than the trend of the last decade. That will still be enough to hurt investors and retirees who do not adapt to it, and enough to create opportunities which intelligent investors and retirees can take advantage of.

Will There Be Longer-Term Problems?

Recently, Fed official Randal Quarles spoke at a bankers’ convention in Idaho, addressing the rise of central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). He addressed concerns that some other country’s central bank might create a digital currency that would upstage the U.S. dollar. We thought his remarks were significant and wise:

“The dollar’s role in the global economy rests on a number of foundations, including the strength and size of the U.S. economy; extensive trade linkages between the United States and the rest of the world; deep financial markets, including for U.S. Treasury securities; the stable value of the dollar over time; the ease of converting U.S. dollars into foreign currencies; the rule of law and strong property rights in the United States; and last but not least, credible U.S. monetary policy. None of these are likely to be threatened by a foreign currency, and certainly not because that foreign currency is a CBDC.”

Our eye went to two items which he noted as “foundations of the dollar’s role in the global economy”: the stable value of the dollar over time, and credible U.S. monetary policy.

These are the two items that some anxious analysts and investors think might be threatened by the extraordinary measures undertaken by U.S. monetary and fiscal authorities to create the inflation they need. Could those measures ultimately dethrone the U.S. dollar and create economic chaos?

The short and simple answer is, “Perhaps, but if they do, it will not be for a very long time, and in the meantime, there are avenues for profitable investment and ways to prepare.”

The strength of the U.S. economy, the depth of U.S. financial markets, and the strength of the rule of law in this country (which treats capital better than almost anywhere else in world) are extremely potent factors — factors which, for now and for the foreseeable future, should override theoretical considerations of future problems.

Investment implications: Policymakers are serious about creating inflation, and we believe they will succeed in creating it. This argues that as we move into the likely enduring post-pandemic environment, investors should focus their attention on assets that can appreciate in an environment with inflation that is above the trend of the past decade — perhaps well above it. That should particularly include growth stocks and enduring disruptive themes (tech, biotech, etc.) that sell at reasonable valuations with high-quality earnings; some materials and materials producers, both industrial and agricultural; and allocations to precious metals and cryptocurrencies. The “reasonable price” caveat implies that investors must be ready to take advantage of declines, and buy dips.