In early June, Chinese ride-hailing giant Didi Chuxing [DIDI] filed for a public stock offering on the New York Stock Exchange. To call DIDI “the Chinese Uber” [UBER] would be an understatement; in fact it might be more accurate to call Uber “the American Didi.” In the past 12 months, DIDI’s revenues were about $25 billion, compared to UBER’s $11 billion; it claims to have about four times UBER’s user and driver base.

Like other Chinese tech giants, it has expanded into many related offerings beyond its core business, including on-demand delivery, car sales and leasing, fleet operations, vehicle finance, and electric vehicle charging. In short, DIDI was a big deal — a gold standard of Chinese tech companies with big ambitions and big growth runways in the markets shaped by China’s technological “leapfrog” into a digital-first future.

Now things have taken a drastic turn — not just for DIDI, but for a host of Chinese firms, especially big tech firms, listed on U.S. exchanges. Huge amounts of investor capital have been wiped out by a sudden paroxysm of suppression from Chinese regulators. It’s not the first time this has happened, and it probably won’t be the last, and it probably won’t last forever, but for now, it is completely changing the calculus for developed-world investors in China, and for many of China’s tech entrepreneurs.

We’ve long been impressed by the creativity of China’s tech entrepreneurs (less so by the foresight and wisdom of China’s regulators), and many U.S. investors have looked to the larger Chinese tech sector as a bright spot of global innovation and growth. So current events have been a shock. Below we’ll walk through some of the background and likely consequences.

Chinese Companies On U.S. Exchanges: An Uneasy Peace

In recent years, many Chinese companies came public on U.S. stock exchanges, as Chinese entrepreneurs sought to tap growth-hungry western capital. There were obstacles on both sides. Chinese laws governing foreign ownership of Chinese companies were skirted by the creation of opaque “variable interest entities” (VIEs) domiciled in places like the Cayman Islands, and U.S. regulators permitted domestic Chinese arms of international accounting firms to perform the financial due diligence required by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for U.S. stock listings.

Neither of these workarounds was really satisfactory. In the final analysis, VIEs did not offer investors the kind of protections and recourse that are typically available to holders of common stock; and Chinese accounting proved over the years to be a shaky assurance of proper financial practice — with many scandals and revelations of fraud among smaller Chinese companies. But the uneasy peace worked well enough for developed-world investors — particularly with large Chinese firms perceived to have the approval of the government, and whose global ambitions made them more likely to steer clear of fraudulent or deceptive accounting practices.

The Uneasy Truce

Given the slow-burning, back-and-forth trade war between the U.S. and China in recent years, it was perhaps inevitable that this modus vivendi would be shaken. We don’t need to rehash this history; there were long-simmering suspicions and resentments on both sides.

The deeper cause, as we have often written, is simply that China’s rising economic strength and geopolitical ambition caused the U.S. to take a different view of the economic and commercial accommodations it had granted in the wake of China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001.

Accommodations that had been made to a smaller and weaker China in the hope of using economic prosperity to encourage its movement towards domestic democratic governance began to look less sensible in the face of domestic authoritarian retrenchment (e.g., Xinjiang and Hong Kong), geopolitical intransigence (e.g., Taiwan and the South China Sea), global ambitions (e.g., the Belt and Road initiative), and offshoring’s long-term negative consequences for the U.S. manufacturing base and economic heartland.

The First Shot Fired

During the first few years of rising tensions, the model that allowed Chinese companies to list in the U.S., and allowed developed-world investors to buy those shares, continued. In December, 2020, however, the Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act was signed into law in the U.S. This Act amended the Sarbanes-Oxley law to require foreign companies listed on U.S. exchanges to face the same accounting scrutiny as domestic companies, by subjecting audits to review by the Public Company Accounting Standards Board (PCAOB). Needless to say, China announced that it would refuse to permit Chinese companies to cooperate with the new law — the only country in the world to do so.

We note that the law was passed by a divided Congress. As we have pointed out many times, this shows that the shift of U.S. policy towards China was not just an artifact of the Trump administration, but spans the party divide.

This law set a process in motion that, unless it were changed, or some other deal were made, would result, within three years, in the ejection from U.S. markets of Chinese companies with a combined market value of almost $2 trillion.

China’s Inevitable Response

The first sign of Chinese moves against U.S.-based offerings were the October and November 2020 crackdown on business magnate Jack Ma, the cofounder of Alibaba [BABA], and his retreat from the public eye. A proposed U.S. offering of BABA’s giant fintech arm, Ant Financial, was shelved, and regulatory heat on Chinese fintech companies was turned up.

On June 30 of this year, DIDI, the next poster-child of Chinese innovation and growth, raised $4 billion in a New York IPO. The IPO was managed by Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and JPMorgan.

Two days later, the Chinese authorities announced an investigation of DIDI, and pulled its apps from app stores. The immediate justifications were “data security” and revived accusations of antitrust violations. It seems the real reason was that DIDI had already been warned by Chinese officials almost four months ago not to go ahead with a U.S. listing… but they chose to do it anyway.

(One wonders whether the due diligence of the bookrunners for the deal uncovered this “discussion” with Chinese authorities. This will probably be a topic that is taken up in class-action lawsuits.)

In the time since, the index that tracks Chinese ADRs trading in the United States has declined more than 44%.

Source: Bloomberg, LLP

“Reining In” Other Tech-Related Industries

In early July, more clouds gathered, as Chinese authorities moved to decimate the country’s burgeoning online education sector. The crackdown promises to be heavy, with Chinese regulators indicating that they see no place for for-profit businesses in the industry, which has become a large one in China. Existing companies have been banned from raising capital; new businesses have been banned from going public. In this instance, the justification was “inequality” — with Beijing maintaining that for-profit companies in education are exacerbating the divide between Chinese who can afford supplemental education for their children and those who cannot.

The rhetoric employed by the government is an echo of something that predates Deng Xiaoping’s embrace of free enterprise — saying that the industry has been “hijacked by capital.” This is a big change in message from anything the Chinese government has projected for many decades.

Further regulatory action has been announced against food delivery and property management companies.

Finally, Chinese fintech leaders Ant Financial and Tencent [TCEHY], creators of dominant payment platforms WeChat Pay and Alipay, have been “invited” to participate in the development of the digital yuan. Since the digital yuan will erode the profitability of the services these companies offer, they are basically in the position of prison-camp inmates being told to dig their own graves while the firing squad stands at the ready.

TCEHY is at particular risk, because they are major investors in many of China’s tech startups — and in fact, owned a 12%+ stake in DIDI. (Another big casualty of the DIDI disaster was Japan’s Softbank [SFTBY], a 21.5% stakeholder.)

For all of China’s tech leaders, what was formerly a wide-open future was just markedly narrowed, as it became clear that an era of wild-west license is coming to a close.

What Comes Next?

Needless to say, these developments have caused consternation among foreign investors. As one Goldman Sachs analyst observed, “Even when you think China risk is priced, it can get worse.”

Of course, regulatory risk is nothing new for China. But the suddenness and severity of the recent regulatory actions obviously pose deep questions for investors.

Obviously, the Chinese authorities are reacting to what they see as life-and-death threats and vital national interests.

First, as they have been saying since the beginning of Xi Jinping’s reign, they are moving from a subservient posture vis-à-vis the U.S. and the rest of the developed world, to a more assertive posture, in which China will claim its rights as a global leader — economically, geopolitically, and militarily. That means vigorous pushback against the U.S., and against elements within China seen to be unreliable in their support of the regime. Obviously, foremost among those are cosmopolitan tech entrepreneurs with access to overseas capital and data troves that could be deployed in ways the Chinese government views as detrimental.

Second, they see specifically that technology companies are a potential threat to Party rule. They have long seen technology itself as a positive tool to be deployed to support authoritarian rule and to create economic growth — but now they may be seeing the power of the big tech firms as a threat, and moving more forcefully to get that power under control before it gets away from them. (They are probably also looking across the Pacific at the profound domestic political power of U.S. tech firms, and seeing a situation they want to avoid.)

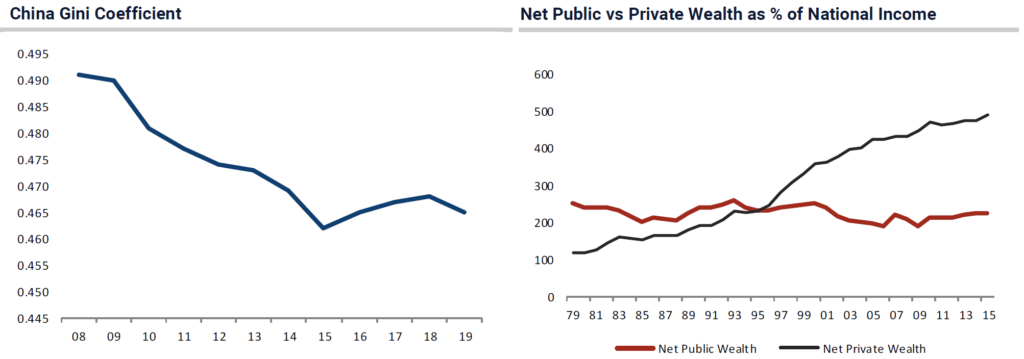

And third, even if technology has been useful as a tool for pacifying the population and creating prosperity, the government may now be coming to believe that the inequality they had long tolerated in their pursuit of technological innovation, may be starting to become a cause of resentment and potential popular unrest.

Investment implications: China dominates the holdings of many broad emerging-market index funds — and indeed, it is often dominant even in the holdings of more specific emerging-market thematic funds and indices. Investors who hold those funds may have more exposure to China than they understand.

The reward/risk ratio of Chinese equities, particularly foreign-listed tech shares, just became a lot more difficult to determine — with the risk side highly elevated and the reward side likely substantially constrained, as the growth leaders are the very companies under particular regulatory threat and pressure. To us, this is another compelling reason to invest in individual securities rather than index funds wherever possible, so as to be able to control such aspects of systemic risk more effectively.

Where that is difficult or impossible to do and ETFs are the only option — for example, with domestically listed mainland Chinese stocks — our belief has been strengthened that China is much more of a trade to be held for tactical outperformance, rather than an investment to be held for long-term appreciation. This is a view shared by the most capable China analysts we follow.

Investors should assess the level of China exposure they have through broader ETFs in their portfolio, and examine what kind of companies are held: tech or non-tech; mainland listed, Hong Kong listed, or U.S. listed.

And finally, with questions about Chinese reward/risk rising in a context of other emerging-market uncertainty, and other growth questions in the developed world, the current Chinese debacle can only strengthen the resolve of global investment dollars, euros, pounds, and yen to find their way into the economy where growth is strongest and capital is best-treated — the United States.