Businesses are facing rising costs, and it remains to be seen how “transitory” those will be. The consensus among analysts and officials has been gradually coming to the point of view we have had since early in 2021 — that inflation would be much stickier than their earlier hopeful (and sometimes self-serving) projections.

Throughout the earnings season, many businesses have discussed their escalating spending on various input costs; these expenditures have skewed towards wages, rather than (for example) towards IT or advertising. In an environment of general economic acceleration, we would expect the latter, so the story peddled by some — that prices of goods and services are rising because of a recovering economy — becomes less plausible.

One earnings call comment that caught our attention concerned the source of rising protein costs in the restaurant industry. The chief financial officer of restaurant company Brinker [EAT] responded to an analyst’s question about chicken costs:

It’s not an issue of [the] number of chickens… This is pretty consistent across a lot of the protein commodity bases… There’s enough supply. It’s a production kink that really is throwing some wrenches into the system and creating that incremental cost.

In other words, the bottleneck here is labor. That is at the heart of the “disrupted supply chain mystery.” And that seems to be the bottleneck elsewhere as well. A recent Medium post by a career truck driver broke down a few of the lesser-known reasons behind the chaos still afflicting the U.S.’ largest ports on the west coast. The bolus of imports caused by the lockdown’s sudden stop and start resulted in untenable conditions for many truck owner/operators who are paid by the load and not by the hour. The writer, a Teamster named Ryan Johnson, observed:

Think of going to the port as going to WalMart on Black Friday, but imagine only ONE cashier for thousands of customers. Think about the lines. Except at a port, there are at least THREE lines to get a container in or out. The first line is the “in” gate, where hundreds of trucks daily have to pass through 5–10 available gates. The second line is waiting to pick up your container. The third line is for waiting to get out. For each of these lines the wait time is a minimum of an hour, and I’ve waited up to 8 hours in the first line just to get into the port. Some ports are worse than others, but excessive wait times are not uncommon. It’s a rare day when a driver gets in and out in under two hours…

Furthermore, I’m fortunate enough to be a Teamster — a union driver — an employee paid by the hour. Most port drivers are “independent contractors,” leased onto a carrier who is paying them by the load. Whether their load takes two hours, fourteen hours, or three days to complete, they get paid the same, and they have to pay 90% of their truck operating expenses (the carrier might pay the other 10%, but usually less). The rates paid to non-union drivers for shipping container transport are usually extremely low. In a majority of cases, these drivers don’t come close to my union wages. They pay for all their own repairs and fuel, and all truck related expenses. I honestly don’t understand how many of them can even afford to show up for work.

We would add some observations that Mr Johnson missed. Further reports suggest other critical reasons for a shortage of truck drivers, including impending decarbonization laws in California that make it a questionable investment to buy a diesel-powered big rig, when those might not be able to operate in the state a decade from now. Bear in mind that such trucks are a huge investment for an owner/operator, often on a par with a house. A further problem is the drug testing regime — the Drug and Alcohol Clearinghouse, since 2020, has taken 91,000 drivers off the road for substance abuse violations. The mismatch between Federal and many newly liberal state marijuana policies is at work here.

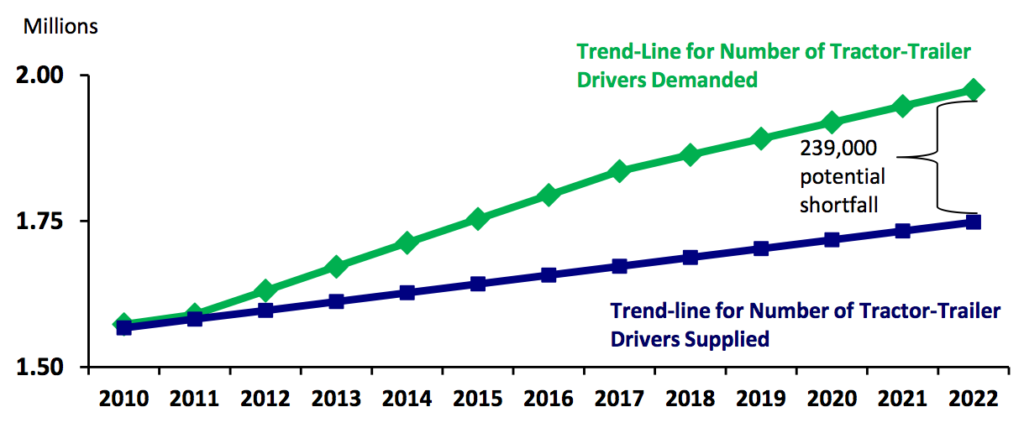

But perhaps the elephant in the room is the American Trucking Associations’ data showing that the average age for a new truck driver is 35 — indicating, as they suggest, that the career is a “last resort” rather than a first choice. Here as in many areas, covid accelerated a trend that had long been in place — truck drivers are an aging cohort, trucking is a tough and demanding occupation in the best of times, and the trials of the pandemic policy disruptions have been enough to make an increasing population of truckers hang up their keys and say “no more.”

Source: American Trucking Associations

(The above chart is several years old, and post-pandemic data will likely show substantial deterioration.)

Digitization is not the only thing the pandemic pulled forward. It also pulled forward retirements, including in blue-collar occupations that have proven to be more important for the functioning of the country than many media pundits understood, and harder to replace. With apologies to the geniuses of Silicon Valley, self-driving trucks are not coming to the rescue any time soon.

This is a further reason why we do not believe rising costs for businesses that ultimately derive from labor costs are going to be as transitory as hoped, and neither will the inflation those costs drive.

A further case in point: the ongoing labor dispute in which John Deere [DE] employees said “no thanks” to a company offer approved by union management. Organized labor in the United States has been in generational decline since the Air Traffic Controllers’ wildcat strike in 1981 and the Reagan administration’s hardball response that defeated it. The pandemic acceleration of demographic labor-force attrition might be the beginning of a revival of fortunes for U.S. organized labor, which has now shrunk to a small slice of the overall workforce.

Last week, we offered some reflections on the political consequences of inflation. A rise in the economic and political power of labor could have similar unexpected consequences. We would not rule out a shift in the internal politics of the Democratic Party, which for some time has been largely shaped by the Party’s left wing. Such a shift would be more grassroots than the policy postures of recent years — dare we say more conservative?

It would also reflect the Republican Party’s transition towards more populist and labor-friendly positions. As we often observed throughout the Trump administration, Trump would come and go — but the dynamics that drove his 2016 election remain in place, and indeed, have accelerated over the past two years during the pandemic. Working-class American voters across party lines felt that they had suffered from decades of eroding income and social standing through offshoring, poorly negotiated trade deals, and social diminishment under an administrative state run by condescending academic technocrats.

We anticipate that labor militancy will increase in coming years. Readers who remember the pre-Reagan era will recall how much more frequent strikes were in those days. With economic forces favoring labor, work stoppages are likely to become more common.

Investment implications: The supply chain snarls and rising costs of the lockdown aftermath are largely attributable to the pandemic’s effects on labor. This is likely to mean that inflationary pressures will be more persistent than the majority of commentators assumed until recently. A structural decline in labor-force participation — a pull-forward of retirement in a number of critical and hard-to-replace industries — could also lead to a revival of fortune for organized labor and have significant, and perhaps moderating, effects on the platforms and political programs of the major U.S. political parties to reflect more closely what we view as a fundamental centrism of the American electorate. If this pattern persists, it will lead us to discount the likelihood of the implementation of further sweeping policy changes on a Federal level, which would have effects on the prospects of a swath of sectors and industries. On the inflation front, we continue to prefer companies with pricing power who are less reliant on labor and material inputs (and particularly labor inputs in the lower strata of the wage structure).